An Analytical Music Blog

Lineage, Signifyin(g), and Sampling in Kendrick Lamar’s ‘reincarnated’

The recent surprise release of gnx follows Kendrick’s almost universally agreed defeating of Drake in the greatest rap beef since Biggie Smalls versus Tupac Shakur. Regardless of his standing as, arguably the greatest, but certainly one of the most profound and nuanced rappers of his generation, I feel the album is slightly less polished and thematically thought-out as his previous full-length releases.

This is not to say, however, that there aren’t many moments of excellence here. One of the tracks that stands out the most to me is ‘reincarnated’, where he discusses the psychological fallout from past-life regression therapy he underwent last year. The themes and compositional concepts here echo the theoretical writings of Henry Louis Gates Jr. on Signifyin(g) (1988). Gates Jr. argues that African American cultural artefacts and practices can be understood as takes on, and deliberate references to, what has come before whilst building on them to evolve artistically and culturally. Kendrick brings into focus the idea of lineage and genealogy as he raps from the perspective of varying Black musical icons.

The first artist he refers to is Tupac Shakur. Kendrick has never obscured his appreciation for the West Coast’s poster boy, exploring Tupac’s ideas on the nature of Blackness and the struggles of being an African-American icon in ‘Mortal Man’ from To Pimp A Butterfly (2015). But instead of a post-humous stitching together of audio interviews in the former, here he samples the drums, arpeggiated guitar and meandering piano melody of Tupac’s ‘Made Niggaz’ (1996).

This sample sticks out amongst the other instrumental timbres on gnx, particularly because of the piano’s plasticity. Contemporary VST is now much more developed than the production apparatus of the nineties’ which is evident here as the sample sounds decidedly synthetic. Now, it isn’t hard to download a fairly realistic sounding piano plugin, have it play a MIDI line clicked into the piano roll, and, especially when buried in the mix amongst other instrumental lines, happily deceive listeners as to its non-acoustic reality.

The explicit artifice attests to its function as referential rather than aesthetic. Kendrick spits his first bars with a sixteenth note flow that resembles the rhythmic fashion of Tupac’s opening bars on ‘Made Niggaz’. As we continue looking at the first verse, it becomes quickly apparent that he is not rapping strictly from his own perspective as he “take[s] it back to Michigan in 1947”. Although he does not make it explicit who he is referring to, it is highly likely he is rapping as blues guitarist John Lee Hooker. Hooker ran away from his parents in Mississippi as a young teen, before settling in Detroit where his recording career eventually took off whilst he was working on a factory line (Palmer, 1981). Kendrick (or John) ends the verse with “died with money, gluttony was too attractive, reincarnated”.

Every time Kendrick yells “reincarnated” he then proceeds to embody another musical figure. He starts the second verse with “another life had placed me as a Black woman in the Chitlin’ circuit”. This woman is probably Billie Holiday. He then discusses Holiday’s struggles with substance addiction, ending the verse with “I died with syringes pinched in me, reincarnated.” This is the last time we here the “reincarnated” motif; the third verse is ended with an exclamation of “’carnated!”. Kendrick initiates the final stanza with “My present life is Kendrick Lamar”, implying we have made our way through the past-life genealogy to his current embodiment.

Interestingly, the ‘Made Niggaz’ piano sample drops out here and is replaced by a bright, beautifully arpeggiated guitar alongside some fluid, embellished piano lines, that are decidedly organic; it sounds like a performer actually played these parts as opposed to them being inputted as MIDI. The basic harmonic content prior to the entrance of these two lines had been repeating throughout; the bass implies an Am7 chord for two bars, followed by a Gsus2 chord for the same duration, which then resolves back to the Am7 and repeats. However, at the point Kendrick declares he is rapping as himself, we get a development of the harmonic content and an omission of the Tupac sample. Am7 plays again, but instead of leading to the Gsus2, we get a borrowed chord of Bmin7 that takes us out of the A minor key previously created through the cyclicality between Am7 and Gsus2. As the B minor takes us to another harmonic realm, we enter the Kendrick’s current carnation as himself.

The piano sample then re-enters as a begins conversation with someone he calls “father”. The themes of lineage here suggest the father figure could be Kendrick’s biological father, but it can also be read as being God, or maybe some sort of unifying amalgam of the lineage he underscores. However, the biblical references that proceed this infer he is talking to his creator as the “father” says:

“I sent you down to earth ‘cause you were broken,

Rehabilitation, not psychosis

But now we here now

Centuries you manipulated man with music

Embodied you as superstars to see how you moving”

The shifting points from which Kendrick outlooks lyrically now here become clearer. Kendrick is imagining the possibility of him being, in essence, the same soul as Holiday, Tupac and Hooker, chosen by God, and reincarnated in a new body each time the dangers of fame compromise one of their earthly bodies. This genealogy of past-lives points at a subjective nature of Black stardom; the pull of destructive temptations is as strong as the joy you provide to your audience. Whether this be substance abuse, greed, or the attacking of your peers, Kendrick infers this special soul was chosen by God as a messianic but prodigal figure.

What is most masterful here, is Kendrick’s use of the Tupac sample. Although it, admittedly is not played throughout the whole song, the moments where it enters or is removed are of most profundity. The sample is playing when he is lyrically exemplifying Holiday, Hooker, and briefly Tupac at the start. Yet, when he announces his current manifestation as Kendrick Lamar, the sample is removed, and we enter new harmonic territory, granting this sonic sense of forward motion. The sample does re-enter in the third verse, but only when he is having the conversation with his “father”. We can understand the sampling of Tupac as sonically marking this idea of lineage, and this is a powerful tool to do so.

On sampling, Joe Schloss writes “it allows producers to use other people’s music to convey their own compositional ideas” (2004, p. 138). Sampling is basically a compositional way of overtly underscoring the idea of musical heredity; a song is made and exists within itself, then someone samples it and it becomes, whilst still embodying its origin, something new. This musical concept is the same thing Kendrick explores lyrically, reincarnation. Sampling is a musical manifestation of Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s literary theory of Signifyin[g] (1988). Other examples include the constant re-arrangement of the jazz standard, or the collage work of Jean-Michel Basquiat: the taking of a source material, and repurposing of it into something new. This creates an overt lineage of art, in the same way Kendrick constructs the lineage of African-American excellence and places himself as the most recent expression of it.

Ariana Grande – ‘imperfect for you’ – A Brief Analysis

Twitter relationship gossip aside, Ariana Grande has released some of the best written pop songs of the last decade. The first five tracks off thank u, next (2019) are stellar examples of catchy, vibrant and masterly writing. They use sound worlds that are completely familiar to a modern audience - the aesthetic mix of pop, R&B and trap is so pervasive to the point of ubiquity. Yet, the structures, chord progressions, melodies, rhythms, and time signatures in most of her songs are masterfully constructed and implemented.

Her latest release, Eternal Sunshine (2024) is, for me, less captivating than her 2019 release. Although, there is a particularly remarkable use of a chord in the chorus of ‘imperfect for you’. Musical writing credits are shared between Grande, Swedish song writing extraordinaire Max Martin, Ilya Salmanzadeh and Peter Cahm. The lyrics were written by Grande and Martin alone and they speak of one’s insecurities and flaws being ironed out by the love of another.

The song sits at around 74 BPM and slowly lulls us through the 3:02 run time with a 6/8 time signature. The first verse starts in E major, only using chords form the key until an F major chord is played after the following line:

“Throw your guitar and clothes in the back seat”

0:06

As we are taking into this transitory modal harmonic space, no melody is sung as the guitar plays it, thus existing as pure musical colour, albeit an unexpected shade. A borrowed chord from the mode of E Phrygian Dominant; this chord doesn’t seem that striking in its first usage. Yet, in the chorus, it is used in a much more arresting way. The first verse then continues to use chords from E major, until it pivots on a G# minor chord to modulate to C# minor for the pre-chorus.

A pivot chord of B major is again used at the end of the pre-chorus to modulate back to the home key of E major for the chorus (0:40). This chorus is the second time we hear the borrowed chord of F major instead of F# (0:50). Sounded as Ariana sings the word “imperfect” it is imbued with much more unexpectedness than the first time, amongst the perfectly predictable trajectory of the tonal chords of E major. It would be a colossal misinterpretation to say that all modal harmony, or chords that exist outside the structures of Western tonal harmony are eternally nods to imperfection. However, the songwriters use other musical devices to pronounce the sudden meander into modal harmony.

F major’s conspicuousness in this harmonic context is intensified because of its situation between the tonic chord of E major. The chorus’ progression starts on E, then goes to F#, then resolves to the tonic of E major. But it is only after that resolution that we hear the F major from Phrygian Dominant, thus allowing a sense of completion to only be thrown a brief, peculiar chordal curveball, until the tonic is then immediately sounded again and the progression continues. Ariana ascendingly arpeggiates F major, melodically highlighting it – something that is not done when the F major is sounded in the first verse. These two concepts are what exaggerate the irregularity of the chord in context.

I will again, reiterate that I am in no means saying borrowing chords from parallel modes has always semiotically reference imperfection; traditionalist eurocentrism is all too often embedded in Western understanding of harmony. However, its situation between the two tonics really does create a remarkable aesthetic response. Technicality of musical structures aside, this chord drips with emotional profundity. As it is played on the word ‘imperfect’, the salience of this chord usage in situ is coupled with this notion of imperfection; beautiful, adequate inadequacy. The chord’s abruptness does serve as synecdoche for the abruptness of anxiety, the limitations of our character, but, overarchingly, how perfection is not needed when you are surrounded by the comfort of the one you love, and they are surrounded by the comfort of you.

Chy Cartier ‘BOSSED UP’ – A Brief Analysis

I first heard Chy Cartier rapping a couple of weeks ago and she soon became my newest favourite. Her voice is unbelievably striking, using a vocal timbre reminiscent of Dizzee Rascal: just below a screech. Effusions of grime aside, it is the flow, particularly in this song, that arrests attention.

She demonstrates a profound playfulness with rhythm. The delivery of two lines in particular is the hardest and most distinctive I have heard in a while. In the hook, Chy spits:

“Bossed up

Twenty-ounce-steak, lobster

Them bitches washed up

Them bitches ancient

Fragrance Baccarat

Me, I’m a stack’a that

Go gets

The niggas vex cah they don’t get no texts

Come up off of Basmati, Canned Beef

Bowl full of Lucky Charms holding up my Van Cleef

But this was no luck”

The line “bossed up” starts on the fourth beat of the bar, inconspicuously embedded within the first verse before it. Yet, as one listens to the rest of the song, it soon becomes apparent “bossed up” is the start of the hook. This structural illusion compliments the wonkiness of her cadence too.

The two syllables are delivered as straight quavers, more or less directly on the beat, with omission of any vocals on the first beat of the proceeding bar. The lack of a rapped word on the following crotchet pre-empts the satisfying crookedness of Chy’s subsequent rapped rhythms. The next three lines are rapped relatively on-beat again.

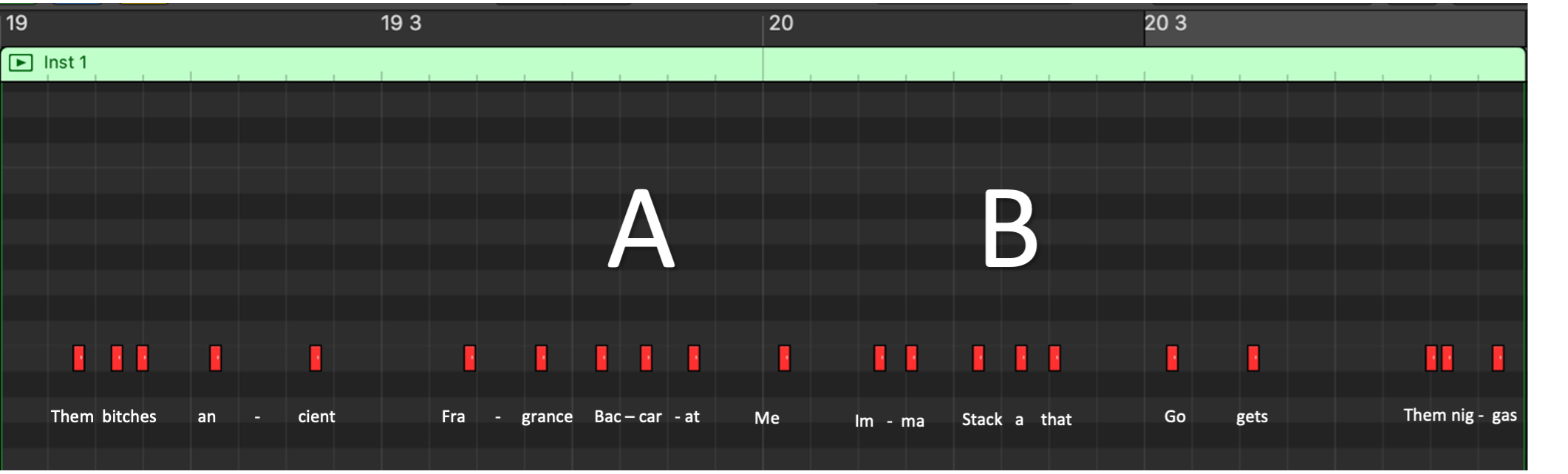

The arresting rhythmic tension comes in bars 19 and 20, of which below, is a rhythmic MIDI transcription:

However, it does show that ‘A’ semi-quaver triplet is more evenly spaced than the B one is. The second syllable of ‘B’ is closer to the third than in ‘A’. The swung nature of this note in the triplet group, creates a metric unevenness. Alongside this, the fact both ‘A’ and ‘B’ triplets start on rhythmically weak quavers lays an off-kilter foundation regardless.

Yet, it is the alignment of words and rhythm that demonstrate young Chy’s mastery. The ‘B’ triplet is rapped so it creates the effect of these syllables being squashed in, unevenly, into this tiny space; she “stacked all that”, if you will. An again, very brief, but brilliant exercise in playing with micro-rhythm; this being the swing of the second syllable in ‘B’, contrasted with ‘A’s relative evenness. Here sonic synecdoche means the vertical stacking of cash is audibly represented by the horizontal stacking of rapped syllables. I can only see bright things for this woman.

The Sonic Relationship Between Supertrap and Hyperpop

I wish to compare the ethos of these two, supposedly similar styles (as the etymology would suggest). However, I concur that justifying a need for comparison based merely on the name of two genres may be a tenuous basis. Yet, the semantics of “super’ and “hyper”, I think, warrant further study. “Super-trap” implies a continuation, an extremification, of the already existing trap genre, as does “hyper-pop” with pop music - they both claim to be progressions of these genre’s trajectories.

Aside from the inference resultant from their names, the textures and timbres in both genres are reflective of each other. Supertrap and hyperpop forefront a decidedly digital sound world, with textures and timbres that can be understood as reflections of the digital realm.

An example of this musical sentiment in hyperpop is the vocal production on SOPHIE’s ‘Immaterial’ The verse and chorus sections are, instrumentally, very similar, looping a syncopated synth riff throughout until it is filtered out and at 2:04 and an acapella vocal is played in isolation. This acapella is pitch shifted, vocoded and autotuned in a truly dizzying way; taking the vocal performance into an alien space that becomes something beyond human. Autotune has been used as a creative, timbral choice since the late 90s, with Cher’s ‘Believe’ being a particularly notable example (1998). But the use of it in ‘Immaterial’, especially with the lyrical rhetoric that anything you want can be ‘Immaterial’ highlights one’s ability to fluctuate and control a portrayed identity. This idea adds a deep profundity to the kaleidoscopic, artificial processing of the vocal.

Casting out attention to supertrap, the introduction to Yeat’s ‘2093’ opens with a hoover style synthesized bass (2024). After a few seconds this timbre playing a legato note, it is then down tuned by a whole tone. A delay is then applied to this instrument. The sustained nature of this timbre would, usually, obscure an addition of delay. However, we can hear the ‘feedback’ parameter of the delay being turned up, resulting in a high screech and then rapid pulses of noise that are audible for a few seconds.

Although, this is a literal example of harnessing the failure of digital sound production tools to create timbres and textures, ‘2093’ quickly refines itself into a more recognisable form than structural weirdness of ‘Immaterial’, with more manageable sounds used after the introduction until the songs terminus. Although, there are further minimal glitchy elements, such as the loudness of the synth note played on the semiquaver after beat three of the main loop, this use of digital musical failure is used to frame the overall aesthetic of the ensuing piece, rather than using digital failure as an obvious and reoccurring musical feature.

One of the influences synonymous with both styles is glitch. The digital aesthetic makes use of the sounds of the supposed failure of digital sound reproduction - distortion, clipping, incompatible sample rates, and lower bit rates. Whereas a glitch artist like Ryoji Ikeda would use these pure digital sounds as the basis for whole compositions, hyperpop and supertrap instead used them in a more superficial sense.

It has been said that glitch music is a turn back to modernism, although this definitely cannot be said for hyperpop (Andrews, 2002). Hyperpop is decidedly postmodern. It takes the musical tropes of pop music and amplifies them, forcing the sounds to crumble under the weight of their own extremity. Supertrap, however, could hardly be called a turn back to modernism, but embodies much less a postmodernist sensibility than hyperpop. This could be for merely temporal reasons: supertrap cannot be anywhere near as self-aware as hyperpop due to difference in longevity between trap and pop. Supertrap, visually as well as sonically, always seems to take itself seriously, whereas, hyperpop’s self-awareness is evident in its Camp, gaudy style.

When we compare SOPHIE’s ‘Immaterial’ with Yeat’s ‘2093’, the mere titles of the songs help elucidate the differences in sentiment of the two genres. The whole of Yeat’s album, aptly titled 2093, looks to the future, and constantly refers to him being in the future. Whereas the themes of SOPHIE’s album are about control, about manipulating the tropes of oneself to something that fits an internal conscious.

The use of digital noise and glitch on Yeat’s record sympathises with Luigi Russolo’s celebration of noise and his philosophy that noise (equivalent to Yeat’s digitalism) is the sound of the future (Voegelin, 2010, p. 43). Yet, SOPHIE’s philosophical use of digital noise and glitch is far more akin to Susan Sontag’s exploration of the artistic style of Camp. Sontag states that “All Camp objects, and persons, contain a large element of artifice. Nothing in nature can be campy” (1962, p. 279). The artifice in SOPHIE’s music is always endowed through the use of digital processing, furthering any natural sound to the point of syntheticism.

We can therefore (deliberately) essentialise the differences in sensibility between these two artists in the following way: Yeat makes the digital realm collapse in on itself to look toward a, possibly dystopian, future, the ensuing power comes from the idea that he can see beyond the present. Whereas, SOPHIE harnesses digital collapse as point of power to show that anything is at the control of the artists.

Three Twentieth Century Classical Pieces

Gavin Bryars - Jesus Blood Never Failed Me Yet (1971)

In his book, American Minimal Music, Wim Mertens makes a point of distinguishing the minimalism of this piece from the minimalist school pre-empted by Cage and forged concretely by the likes of Reich and Riley. I agree with Mertens’ distinction – this piece is minimal in form and structure, but does not attempt to pursue the autonomy of sound that the minimalist movement did.

Instead, it frees the voice of homeless man singing that underpins all of the composition. The unnamed man sings a brief, repeated refrain of:

“Jesus’ blood never failed me yet,

Never failed me yet,

Jesus’ blood never failed me yet,

That’s one thing I know,

For he loves me so”

After a few repetitions of the recording in isolation enter glacial strings. These strings paly a harmonic progression that gets progressively louder and dense as brass enter to fortify the wall of sound. The slow crescendo over the piece’s 30-minute run-time is evokes the slow rising of the sun.

The brilliance of this piece rests in its simplicity. Post-rock bands like Mogwai and Godspeed You Black Emperor make use of this crescendo form. But here it is done with such care and sensitivity that you barely notice each repetition’s accentuation of volume. Pauses in the arrangement also come at masterful points, allowing us to breathe amongst the constant swathes of sound.

Towards the end of the piece, the instrumentation comes to overbear the dynamics of the recording. In the recording of the man exists equal parts hope and despair of which, through the obscuring of the singing by the instrumentation is then nullified. Harking back to my sunrise simile, the composition makes me feel that we can hope and despair all we want; the sun will rise, the earth will continue to be long after our joy, pain, and suffering. Yet, that is not to say there is beauty in our hope.

Gyorgy Ligeti - Requiem (1965)

Ligeti’s Requiem is truly haunting and oppressive– in the best way a piece of music can be.

The second movement, named after the ‘Kyrie’ prayer, drowns us in polyphony so complex that, it at times falls under the weight of its own convolution. Ligeti has called this technique ‘micropolyphony’.

Instruments emerge from the mass like wriggling tentacles evolving from their own entanglement. Various of Ligeti’s works were famously used by Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey. This is an excellent choice of music. Contrary to the suggestion that comes with the name, I feel there is no representation of any kind of earthly god in this piece; only the unbounded infinity of the cosmos. Ligeti’s use of silence here also speaks of the interstellar; the silence of space’s vacuum barged out of the way by massive walls of sound; massive planets, or even something more beyond our understanding.

Steve Reich - Music for 18 Musicians (1978)

This piece is undoubtedly an outlier in Reich’s life work. Although still an embodiment of his typified interlocking, phase-shifting rhythmic cycles, this is his most extensive use of harmony in any of his previous pieces. Yet, in the way we have come to expect from this pioneer of the New York school of minimalism, the use of harmony is methodical, shifting only at the most effective moments to draw one’s emotions as musical colour washes over glacially.

The piece starts in Reich’s usual domain, two percussive instruments playing in unison. As the metallophones play the same notes, staccato strings enter playing the same note as the first one we heard. These quaver string lines grow out from the crotchet pulse played by the percussion players. The two metallophones shift out of rhythmic phase, arguably the most idiosyncratic watermark of Reich’s compositional technique.

I admit I have struggled with the lack of harmony and melody in Reich’s pieces before. The metric and phase experimentation of Drumming (1971), although dazzling (and the closet thing akin to a psychedelic trip of which the active ingredient is rhythm on planet earth) the methodical nature of its progression, and the lack of harmony and melody, leaves a clinical, slightly unemotional taste in my mouth.

New Blue Sun and Pitchfork

Recently, I watched a fascinating and thought-provoking GQ interview with Andre 3000. Last Friday, he broke his period of extended musical silence with his release of New Blue Sun - an ambient woodwind-led record featuring spontaneous experimentation with a wide array of flute-like instruments (2024).

Containing absolutely no rapping, the general sentiment from online discourse surrounding was one of disappointment. Andre’s veer into ambient, instrumental music, for some, felt like Andre was starving people of what they expect from the Atlanta artist.

The stylistic and instrumental disparity between this and his output with OutKast are not just the only things that contribute to the strikingness of the release. The fact that all the recordings were improvisatory furthers the departure from his previous work. He proclaims “it wasn’t planned we didn’t talk about how we gonna use these chords. We just talked about feeling”.

The methodical, systematically composed hip-hop records of his past, is shed in favour of a less restrictive, more reactionary mode of music-making, abandoning musical structure and languages such as chords in favour of more abstract methods.

Pitchfork’s review of the album, however, categorised it as a “rap/experimental” album, even in lieu of the fact there are no rapped words, or even words on the album. This raises some very interesting questions. The most obvious being - why label this a rap album?

The obvious answer is that Andre 3000 is, to many hip-hop heads, one of the greatest rappers of all time. Yet, an ignorant mileu results from this, especially when the title of the first track is ‘I Swear, I Really Wanted to Make a 'Rap' Album but This Is Literally the Way the Wind Blew Me This Time’.

In response to questions about the omission rapping on the album, in the GQ interview, Andre says “sometimes it feels inauthentic for me to rap…I’m 48 years old and, not to say age is a thing that dictates what you rap about, but in a way it does.” He then jokes about how he could rap about getting a colonoscopy or his deteriorating eyesight.

Of course, many rappers of a similar age to him still rap about the same themes that they did when they released music in their early twenties - but Andre, at the moment, wants to progress beyond his creative youth.

At the extreme, it could be said that the blinkard labelling of this record as a ‘rap’ one is racist.

Looking at this in the most, admittedly, cynical racialised way, it links to seminal hip-hop scholar Tricia Rose’s model of the “gangsta, pimp, hoe trinity”. In The Hip-Hop Wars, she argues that since the 1980s, the thematic and lyrical content have hip-hop has been squeezed into the categorisations of the trinity (2008). To elaborate, most commercial rappers speak from the perspective of, and construct their identity as either, a gangsta, a pimp, a how, or a combination of the three.

If we look at the popularity of something like drill, we can see that, although by no means a totalised notion, there are many artists, and even whole scenes, that seem to be confined within this topical enclosure.

Rose argues that forces such as the white record industry and hip-hop’s mainly white listener-base have entrenched this trinity. This becomes more poignant with Bourdieu’s theory of the Field of Cultural Production - how art made in a society can only be consumed within the lens and rhetoric of the society in which it is produced (1994). Therefore, the racist stereotypes of black people are slowly embedded into rapper’s identity construction as this is what sells more. This is because it aligns with some of the negative, white systematically constructed ideas of what the black community are allowed to express and narrate.

In the same sense, when Andre makes a point of, at least for the time-being, departing from his musical past and exploring music that is culturally distant from the trinity, it is still labelled a ‘rap’ album by the powerful actor that is Pitchfork. If we look at this on the same plane as Rose’s trinity, the parallels become apparent; it is rendered troublesome for a rap musician to branch off to genres not as closely associated with stereotypes of blackness, like hip-hop.

Again, this is to look at this act in incredibly a cynical light. However, society’s pigeonholing of black artists is here rendered blatant in the most glaring and ironic fashion.

There are so many more ideas to explore that are discussed in the GQ interview and I would encourage any music fan to watch it. Amongst these include the contrast between nature and the typically urban geography of most hip-hop scenes, ageing rappers, and the fluctuating subjectivity of authenticity. On the most evasive latter, this is what Andre felt was the most authentic record for him to make. The hip-hop artworld seems to demand authenticity, yet the arbitrary confines of what is ‘authentic’ to hip-hop fans here, are incredibly constricted.